Teddy Bergman. Credit Blair Mezibov.

TEDDY BERGMAN is the artistic director of Woodshed Collective, one of the country’s premier immersive theatre companies. Since 2006, the company has presented large-scale theatrical events, including Twelve Ophelias, performed in McCarren Park Pool in Williamsburg, The Confidence Man, adapted from Melville's novel and performed on a decommissioned steamship in the Hudson River, and The Tenant, adapted from the novel and film and performed in a five-story 19th-century parish house on the Upper West Side. Most recently, Woodshed Collective presented the critically acclaimed Empire Travel Agency, a grail quest criss-crossing Lower Manhattan. They are currently under commission from Ars Nova and the Ma-Yi Theater Company for a new immersive theatre experience. Driven by the belief in the combined power of stories and architecture to break down the barriers of everyday life, Woodshed Collective aims to create genuine awe.

“We understand immersivity as an expansion of performance to include the audience in the envelope of the show. ”

Odyssey Works: What are you trying to do with your work?

Teddy Bergman: Woodshed Collective exists to make ambitious theatrical worlds that invigorate our audiences' imaginations.

OW: How do you understand immersivity? How does it work and what is the point?

TB: We understand immersivity as an expansion of performance to include the audience in the envelope of the show. This can mean a lot of things. It can include 360-degree design, direct address, game play, physical engagement of the audience...but more than anything, I think it rests on an awareness that the audience is there, and that the nature of our relationship to them can't be simply assumed.

“We want the scope of our shows to move physically, emotionally, and intellectually beyond what you thought you were getting into, and possibly beyond what you thought a show could or should be.”

OW: You say that your productions aim to generate awe. Can you tell us more about that?

TB: Maybe "sublime" is a better word, in the sense that sublime experiences tend to have ambitious scopes. In our case, we are aiming to have the power to threaten your predetermined idea of what a performance can entail. I think that starts to get at an idea of awe. We want the scope of our shows to move physically, emotionally, and intellectually beyond what you thought you were getting into, and possibly beyond what you thought a show could or should be.

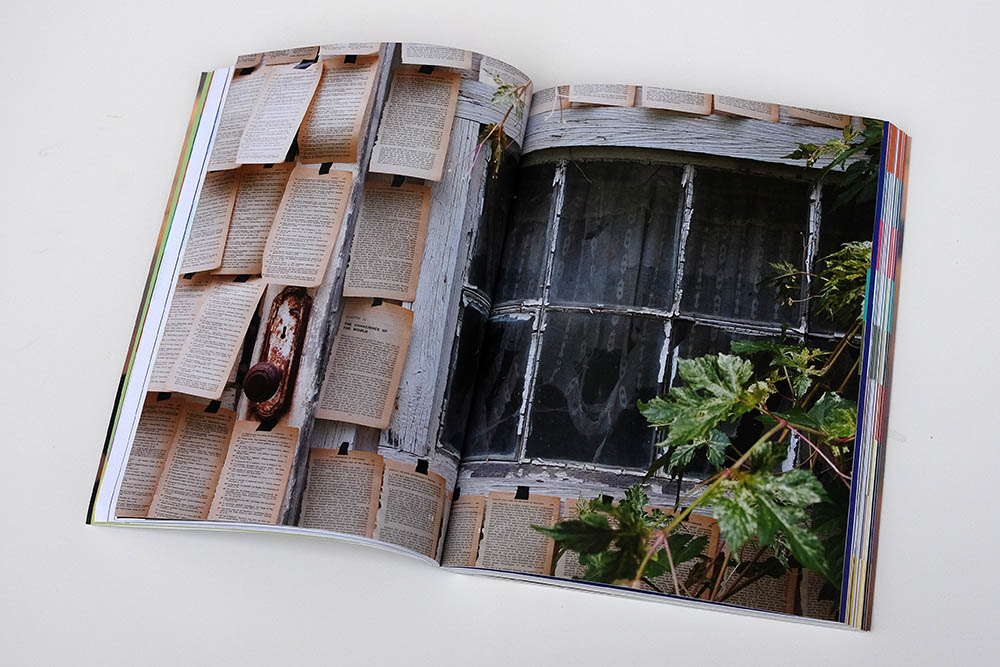

A scene from Empire Travel Agency, a 2015 immersive production that took place throughout Lower Manhattan. Credit Ben Fink Shapiro.

OW: How does the “set” of an immersive play differ from the set of a traditional play? What is the role of architecture in your work?

TB: We tend to believe that all work is site-specific: a church, a boat, a black box, a white box, and the Booth Theatre all carry with them unique histories, and everyone has certain feelings and assumptions about them. Since we think immersive theatre is about including the audience, we take into account the relationships that people have to the spaces we work in, and we incorporate those histories into our shows. And architecture is a major collaborator in our work.

“ We try to create conversations between buildings and texts. ”

OW: What is your process for developing a piece?

TB: We talk and argue a lot. We read. We work with writers to generate material. We talk a lot more. We find spaces. We try to create conversations between buildings and texts. We help design the script. We talk a lot more. Then we starting drawing and rehearsing and building. Then we talk a lot more. Then we have previews. Then we talk a lot more and fix as much as we can. Then we run out of time and open the show and hope for the best.

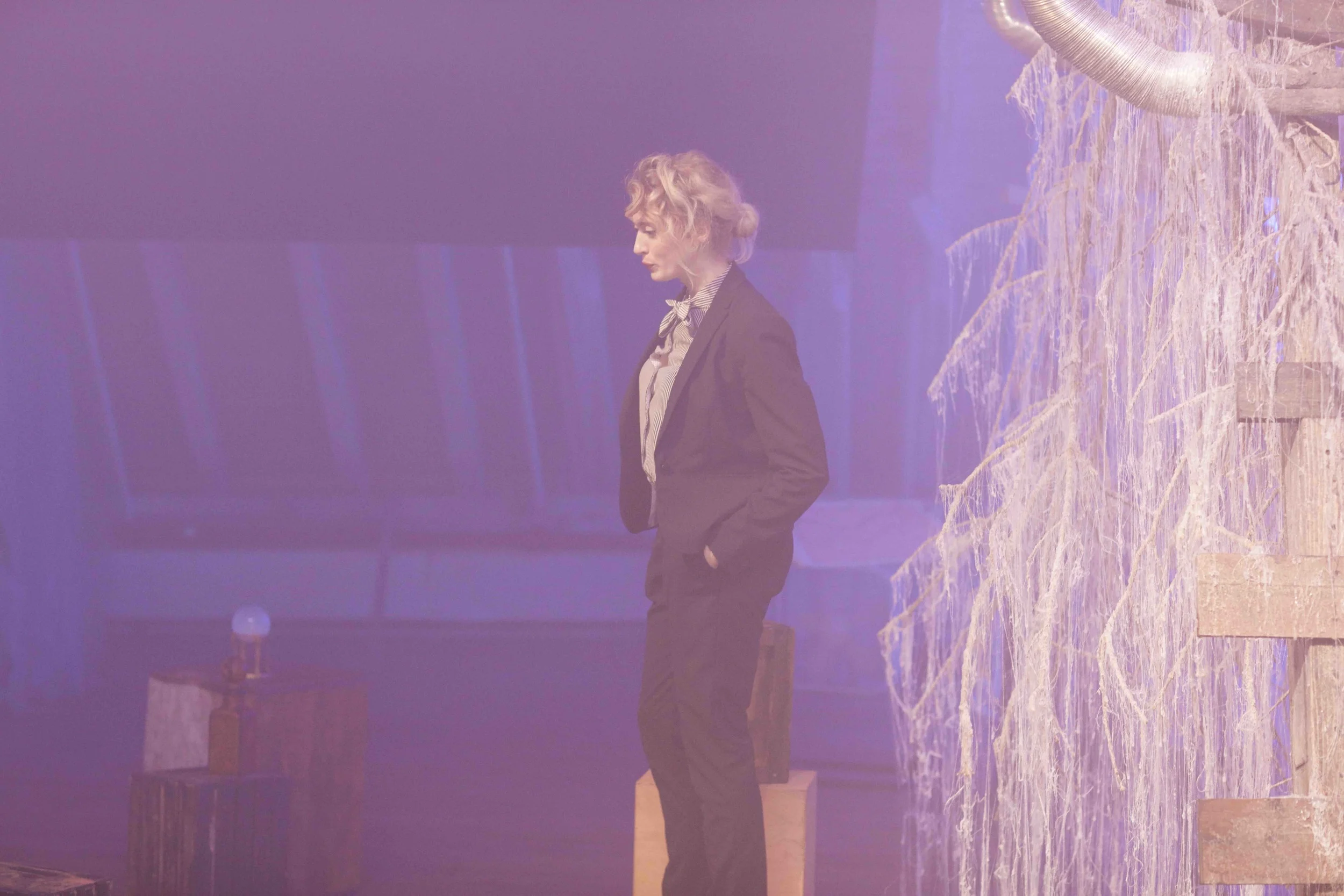

Another scene from Empire Travel Agency. Credit Ben Fink Shapiro.

OW: Who are your influences? Can you describe an experience in which art changed you?

TB: Some of the people and institutions we love are En Garde Arts, Guy Debord, Richard Schechner, Herbert Blau, and Olafur Eliasson. Eliasson's immersive installation The Weather Project at the Tate Modern changed my life. It was a synthetic yet natural public space that nourished, humbled, and inspired every person who walked into it.

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.