Sarah Dahlinger, Danny Crump, Micah Snyder, and Stephanie Wadman of Springboard Collective. Credit Danny Crump.

Springboard Collective produces collaborative, site-specific, interactive, and immersive sculptural environments. Utilizing experimental and imaginative approaches to everyday materials, their installations focus on transforming the physical and psychological aspects of fun through socially engaged events. Their works include Good Humor (an ice cream-making extravaganza), Total Limbo (a fanciful fort), and Soft Surplus and Soft Surplus+ (inclusive playlands). Springboard Collective is directed by Danny Crump, Micah Snyder, and Sarah Dahlinger, and is also comprised of Stephanie Wadman and Barry O’Keefe. Contributing artists include Todd Irwin, Siavash Tohidi, Matt Hannon, Juniper Nova, and Ryan Davis.

“It’s not about me or you, it’s about us. ”

Odyssey Works: What led you to your current approach to art-making? How did you start breaking traditional molds?

Springboard Collective: Springboard Collective started in graduate school at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. Danny had done a residency at Flux Factory in 2014, and got inspired by all the collaborative work happening there; it dawned on him that you could get a lot more stuff done faster and be more improvisational with other people. So he proposed starting a kind of band where we would make collaborative art shows. We were all a bit disillusioned with the isolation of the grad school grind, and we wanted to experiment without the pressure of individual authorship. We wanted to let ourselves be really playful with materials and with ideas without overthinking them beforehand. So we began making these ambitious spectacles with a little bit of painting, a little bit of sculpture, and some kind of social interstice all coming together.

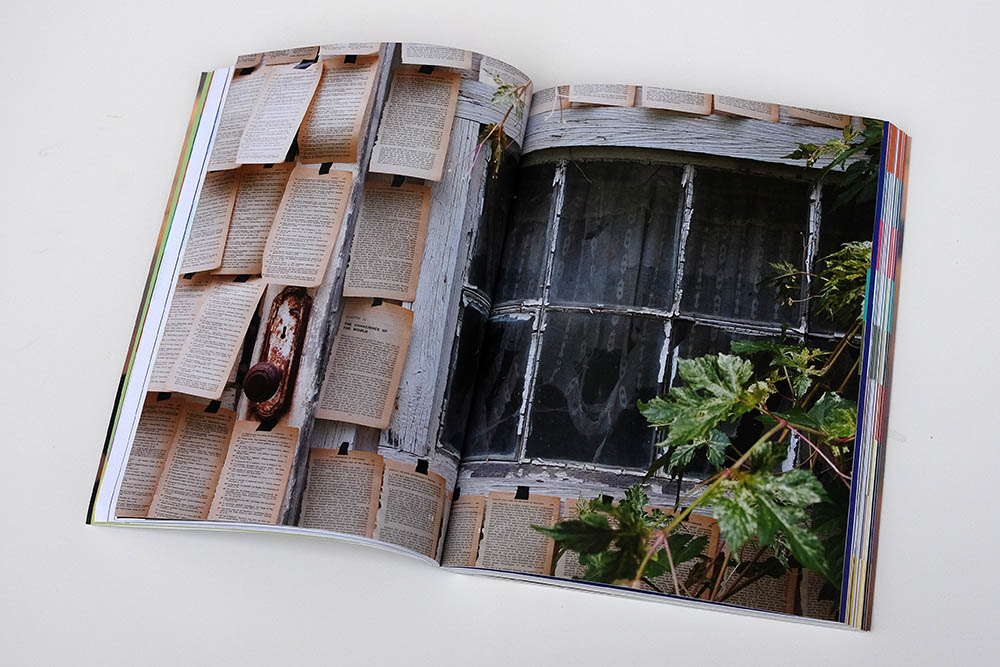

Good Humor, 2015. Credit Danny Crump.

OW: Tell us about your process.

SC: We all bring different skill sets to the table and we are continually pushing and pulling and learning from one another. There are specific things that one of us will get obsessed with doing, like individual videos, but part of the process of working collaboratively is to surrender ownership, and to share credit and responsibility. It’s not about me or you, it’s about us. We tend to work on tight timelines, so it’s a really intensive work period. We might plan a project for three weeks. We usually have a big brainstorm on a big piece of paper, and we just write down every idea that anybody comes up with. And then we figure out how we’re going to fit it all together. We mock up the bigger structural elements, sketching things out in real space. We often have only a few days to build the whole entire thing. So there’s a lot of thinking, then a lot of work, and little sleep. And that’s liberating because it's gestural and fast and we don’t have to nitpick all the little details. We follow the impulse, follow the imagery, follow the materials, and just let those lead us wherever they go.

“We aim to be impish.”

OW: “Fun” is a word you frequently use to describe your work. What does this mean to you?

SC: We aim to be impish. Our pieces give people permission to act a little crazy and be a little weird, which ends up facilitating fun and togetherness. We are creating a new sort of environment that’s a land of escape from actual reality, and the levity of it is refreshing. The things we reference, like ice cream, bouncy castles, and mazes, are all very playful and childlike. One reason we have for working together is wanting get back to a childlike sense of making, and being really open and fearless. It helps people get out of the day-to-day. A lot of times when you go to shows and museums, you’re still contained in yourself, you’re still reserved. But if you have box of costumes, and you put on a wig, and you get thrown into this tiny area where there are 20 people jumping and everything’s going crazy, it facilitates this experience of breaking free and letting loose for a minute. Another thing about a lot of our work is that the pace of people moving through the space is totally different from a typical art-viewing experience. When you walk into an art space, you typically slow down, but all of our shows have this buzz to them. People are really moving around, getting comfortable, getting immersed.

Good Humor, 2015. Credit Matt Hannon

OW: Can you speak more to immersivity and interactivity? What do those words mean to you and why are those elements that you want to include in your work?

SC: The installation format is nice, because you’re not dealing with one material or one medium. Everything all has to work together. In all of our pieces, we’re making something that is interactive because we want to give ownership to the people that are coming to become a part of it. We set up this template for them to inject their own creativity into. They’re churning the ice cream that they’re going to taste, they’re making the sculptures that they’re going to take home. It’s an extension of the process of making to the audience. And it’s a really awesome kind of leveling of different hierarchies of people. Our environments are something that you come and interact freely with. There are no rules. And immersion is necessary because it’s a break from reality. We all need to have moments of escape from whatever pressures we experience, so we provide a space that you can step into and, at least momentarily, be liberated. It’s an offering of a space to be together and work together, and that’s a genuine gesture on our part. If you look at the headlines recently, our type of fun, cheeky event might be just the type of thing that we need right now. In our work, nothing’s too serious.

“We’ve learned that you can make art out of anything if you just put enough effort into it and belief behind it.”

OW: In interactive environments, where do you locate the art?

SC: All of it is the art. And we don’t keep track of any individual’s physical input into a piece. That’s the beauty of it, that it all sort of melts together.

OW: Why create experiences?

SC: We do have relics from our pieces: the objects produced as part of the event. Those have spread out—some people have taken them home—and they do carry a little bit of the energy from the show. But it’s hard to describe all the stuff that happened in any one of our pieces. You really had to be there. We’ve learned that you can make art out of anything if you just put enough effort into it and belief behind it. We start from kind of silly ideas, but then take them to a level where there are much more interesting questions being opened. And the overall experience of the event is where that magic happens.

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman.