Clarinda Mac Low. Credit Ian Douglas.

Clarinda Mac Low was brought up in the avant-garde arts scene that flourished in NYC during the 1960s and '70s. Mac Low started out working in dance and molecular biology in the late 1980s; she now works in performance and installation, creating participatory events of all types. Mac Low is the executive director of Culture Push, a cross-disciplinary organization encouraging hands-on participation and hybrid ideas.

Odyssey Works: How do you understand immersivity and interactivity? How do they work and what is the point?

Clarinda Mac Low: In the realm of theatre and art, immersion and interaction are, to me, two very different propositions. I see immersion as a sensory bath, or flood, shifting perceptual terrain through a number of different techniques. Interaction doesn't require immersion, but they sometimes go hand in hand. Interaction can take a million different forms. It can be as simple as a conversation between strangers, and as complex as a highly responsive environment programmed to sense human presence and shift accordingly. Also, I'd bring up one other term here: participation. I see participation as an invitation to an audience to become co-creators of a situation. As with interaction, this can act on many levels, from a full collaboration to a brief contribution. When a work is participatory, this means the interaction between the originating artist(s) and those who come to the experience is what completes the work.

OW: Why create experiences?

CML: Everybody creates experiences. It's what humans do with each other. If by "experience" you mean a live work that moves through time with an audience instead of a more static work that's fixed in place, it's because I see experience as a common denominator. We all experience time passing, and we all have relationships to others and to our surroundings. Highlighting these states, provoking thought and action around our modes of existing, and allowing time for contemplation of these issues seem like valuable acts to me.

“I create accessible mysteries designed to reach under the ribs and connect to the phantom organs of empathy and decisive action. ”

OW: What are you trying to do with your work?

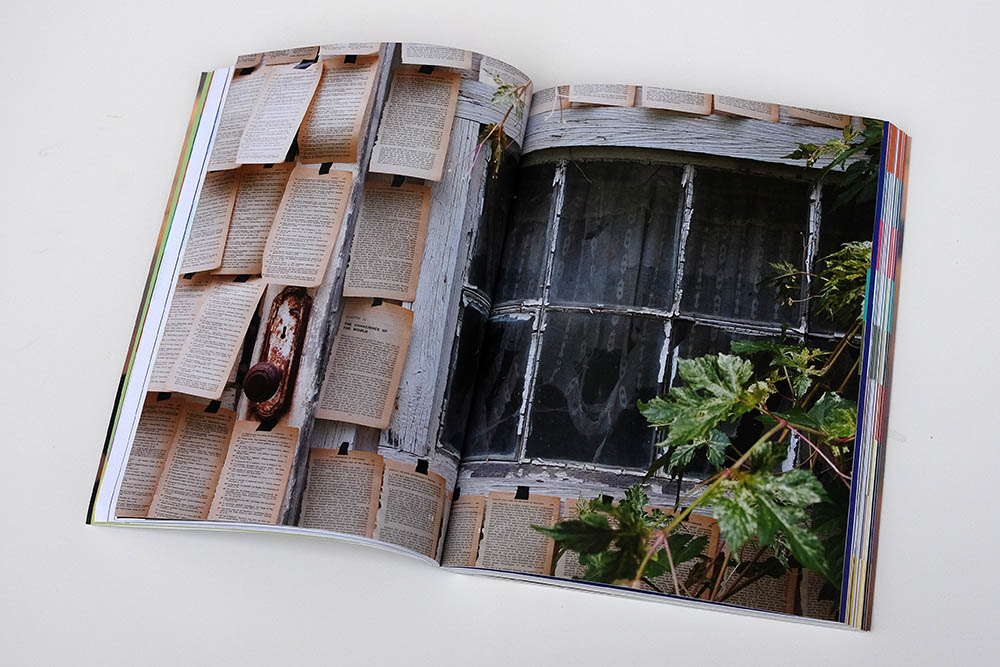

CML: I work to generate situations where the viewer and viewed mutually affect each other, and create experiences that wake up the body and mind. I explore hot subjects through a cool lens, using the scientific method to expose the ways we exist physically with each other, with technology, and with history. I create accessible mysteries designed to reach under the ribs and connect to the phantom organs of empathy and decisive action. My work deals with real-world issues, and it is hard to pin down and categorize. Some of my recent artistic experiments were “Free the Orphans,” which encouraged people online and in public to adopt orphan works (creative works whose copyright holders are impossible to identify); “The Year of Dance,” an exploration of dance performance as ethnography with data analysis; “Cyborg Nation,” where a cyborg interlocutor acted as a connection between human and machine worlds; and “River to Creek,” a roving, participatory natural history research tour of North Brooklyn.

Participants in "River to Creek" wearing sponge shoes to replicate the experience of walking in the marshlands that once occupied North Brooklyn. Credit Carolyn Hall.

OW: What is the collaboration between artist and audience as you see it? Where is the artwork itself located?

CML: For live art, there is always a collaboration, even if the audience is sitting still, watching a performance on a proscenium stage. Anyone who has ever performed or directed work in that context knows that the watchers profoundly change the watched. When I worked more in theatrically based performance, I always located the artwork in the electric connection between artists and audience. Now that audience members are often direct collaborators in my live artworks, the art is still in that connection, but it's also in the creation of the actual experience. We ourselves become the artwork, and our relationships are visible, tangible, and available.

OW: What is the role of wonder and discovery in your work?

CML: My work is based in somatic practice. By involving the audience in an actively physical decision-making process, I create a variety of situations and environments. I rely on a grab bag of tools that emphasize the intangible, including installation, media and technology, performance, dance and other physical action, directed wandering, unscripted conversation, and imaginative play.

A performance of 40 Dancers do 40 Dances for the Dancers, in which 40 people interpreted instruction poems from Jackson Mac Low's The Pronouns: A Collection of Forty Dances for the Dancers. Credit Ian Douglas.

I often reframe our relationships to architectural space and to urban public interactions. I create interventions into everyday life and infiltrations into unexpected sites in a wide variety of communities, from the streets of Lower Manhattan and the Queens Botanical Garden to an abandoned church in Pittsburgh and a park in Siberia. I try to engage audiences in the context of their real lives and ask them to interact differently with each other and with their surroundings.

“I saw the value of going beyond beauty, beyond expression, even beyond a certain conception of ‘human.’”

OW: Who are your influences? Can you describe an experience in which art changed you?

CML: Whenever I'm given this kind of question, Robert Smithson always comes to mind. Then I feel like that's not right, because what changed me was not Smithson's art per se, but the writing he did around that art. Then I feel like it's fine, because his writing about his art was also his art, and his ideas are an artist's ideas. Smithson's work opened a world of possibility to me. After many years of existing within an avant-garde arts context, as the child of an experimental poet and composer and a visual artist, through Smithson I finally got it—I connected to my legacy. I saw the value of these strange and stringent principles I'd grown up with. I saw the value of going beyond beauty, beyond expression, even beyond a certain conception of "human." I am also influenced by the intensity of physical experiences and personal relationships engendered by a long-term dance practice. Working as a professional movement artist for many years gave me access to ways of being and relating that are unusual, rare, and tremendously valuable.

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.