That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.

ON THE ART OF CONNECTION

by Ana Freeman

“It is through the possibility of intimacy that the experience of art can be truly transformative.”

"The desire for connection and the impossibility of it,” said Jim Findlay in our latest interview, “pretty much sum up the whole of human experience, from the criminal to the holy.” Since taking over the editorship of this interview series last January, I’ve spoken with more than a dozen artists. They’ve all had very insightful things to say, but none have stuck with me more than this particular comment. I’m inclined to think it’s true that a desire for connection is at the root of, well, everything. However, I don’t quite agree with Jim that connection is ultimately impossible. I would say that it is rare, but still possible. While we can perhaps never fully know or be known by another person, we can at least feel glimmers of what Marina Keegan called “the opposite of loneliness.” There are many means we have for reaching towards those glimmers. I have recently been working on withholding judgments on the myriad ways people have found to feel whole in the world: to use Jim’s terms, one person’s "criminal" is another person’s "holy."

I moved to New York City about two years ago. It is a cliché to talk about feeling alone in a crowded city, but I have noticed that many people I know do seem to feel disconnected, despite most of us interacting with many people on a daily basis. There are multiple possible explanations: the rise of technologies that enable communicating in impersonal ways; alienation resulting from an urban, capitalist, and competitive environment; rising rates of clinical depression; and the recent inauguration in the United States of a particularly oppressive administration. The extreme political polarization of our country and the violence in our world seem evidence enough that disconnection is not a problem unique to New York. It’s also possible that it has become more popular to talk of a perceived lack of community in recent years because increasing numbers of people have the resources to protect themselves from more pressing practical worries. Nevertheless, we are living in a time where the seeming impossibility of connection is especially potent.

I’ve always believed that art is perhaps more particularly positioned to address the universal human need for connection than most other experiences. But then, where’s the human connection in an abstract painting? There is some message being passed from artist to viewer, of course, but it may be more of an aesthetic or conceptual message than a heartfelt one—more akin to receiving a text than to gazing into someone’s eyes. So though all art is communicative, some of these communications are more intimate than others. It is through the possibility of intimacy that the experience of art can be truly transformative.

Odyssey Works’ first principle is to begin with empathy. For us, this means that we begin the process of creating an Odyssey by extensively researching and interviewing our participant, in order to get to know them as much as possible and gain an understanding of what life in their skin might feel like. It also means that the first intention of the work is that it be designed from the point of view of the participant’s experience, rather than our own. This is the only way for us to make an experience that is truly for and about one person.

I was the production manager for Pilgrimage, the Odyssey we created last November for Ayden LeRoux, our assistant director. Early into the process, I found myself Google-stalking Ayden and constantly thinking about her and how she might react to various pieces of the experience we were planning. For example, when writing couplets that Ayden would find hidden in the New York Picture Library, I adhered not to my own poetic sensibilities, but to what I knew of Ayden’s tastes and history.

The Odyssey centered around Ayden’s knowledge that she carried a gene that put her at high risk for breast cancer. This was not an experience I shared, though I have had medical problems of my own and could relate to the sense of being betrayed by my body. During the planning for the Odyssey, I thought a lot about how it would feel to be in this situation.

When watching a movie or play, there’s a certain process that occurs by which, for the length of the piece, you become the protagonist. The character becomes your avatar for navigating the fictional world, and you share their emotional, intellectual (and sometimes physical, in the case of immersive or VR work) experience. In Pilgrimage, Ayden was the audience member, and I was one of the creators of the work, yet I found myself seeing through her perspective in a similar way, both when planning the Odyssey and during it. Since we spent months creating the piece, this was an experience of prolonged and deep empathy unlike anything else.

Ayden is carried through Brooklyn Bridge Park during her Odyssey. Credit Katy McCarthy.

The fact that Ayden was a real person was also key to this. Imagined characters and situations are often complex and potent, but they can only go so far. Sharing in a character’s experience can be very moving, but I do not believe a relationship with an artwork can compare to a human relationship—unless that artwork itself constitutes a genuine human relationship.

It is for this reason that Odyssey Works strives to create real, rather than make-believe, experiences. Just as an Odyssey is based on a participant’s life, so the Odyssey comes to exist within the real world. Though an Odyssey is composed of scenes, those scenes are not populated by actors, but rather by real people interacting with the participant.

In one scene during Pilgrimage, I gave Ayden a talismanic necklace as she walked across a bridge leading to her final destination, the site of her pilgrimage. As she walked towards me, there was a moment of recognition between us. I recognized her, of course, because I’d been waiting for her, and all my energy was focused on her imminent arrival. But she also recognized me—I was someone she already knew, and she knew I had a role in creating her Odyssey. So I both saw her approaching and saw her realizing that it was me standing there once she got close enough.

I’ve found that acting in front of people I know can be awkward, because they recognize me in spite of the character I’m playing, and this can feel like it threatens the performance. The mutual recognition I felt with Ayden did not threaten the experience, but actually enabled it. Looking back at that moment, I feel that I shared a piece of Ayden’s real journey, not that I played a part in an immersive play created about her journey.

Ayden and I have never sat down and had a long conversation, but I still feel close to her, and protective of her, and like I gave her something that I am proud of giving. I felt privileged to be allowed such deep knowledge of someone. I dove into and explored her experience not because I am her close friend or family member or lover, but simply as in end in itself. In some way it’s the arbitrariness of it that made it so powerful. To partake in someone’s Odyssey is to know that we are all connected, or at least that we can be, if we work at it.

In the spirit of connection, we decided to start this blog in August 2015 to interview artists with similar intentions to our own. Last year, Princeton Architectural Press released a book about our theory and practice called Odyssey Works: Transformative Experiences for an Audience of One, by Abraham Burickson and Ayden LeRoux. If the digitization of communication is one cause of alienation, it also has the power to connect people all over the world, and through the book and this blog we’ve hoped to begin an inclusive conversation. Over the last couple of years, we’ve spoken to conceptual artists, experience designers, performance artists, experimental musicians, game designers, theatre-makers, and culture-creators of all stripes. Via email, phone, and fountain-side conversation, these artists have told us about their ideas, inspirations, and processes. Though we would love to continue the series forever, it is time for us to bring it to a close for the time being. We’ve found a significant sense of solidarity through engaging with like-minded artists, and every one of our interviewees had something new and enlightening to add to the dialogue. With that in mind, I’d like to highlight just a few of the interviews that particularly contributed to our understanding of intimacy in art.

Our interview with Olive Bieringa offered us a stunning view of what making art that stems from empathy can look like. As co-director of the Body Cartography Project with Otto Ramstad, Olive has created several one-on-one dance projects. In her words, this kind of work is a way to “practice being present with another person.” Through movement, artist and audience member give and receive their perspectives and come to a place of mutual understanding. This performance structure facilitates an exciting reciprocal dialogue that disrupts traditional notions of the roles of dancers and audience members.

Kendra Dennard performing with the Body Cartography Project. Credit Sean Smuda.

Christine Jones’ work demonstrates a similar kind of mutuality. Her Theatre for One series consisted of private performances shared between one performer and one audience member. In this model, theatre is not a spectacle or a transaction, but a genuine exchange between two people who share a particular slice of time with one another. She is “an artist who uses intimacy the way a painter uses paint…to make people feel seen, and sometimes…loved.”

Intimacy can go even further when the narrative and symbolic material of the art comes from real life. Tiu de Haan is a beautiful example of this. As a celebrant, she designs experiences for people around major life events, such as deaths and marriages. By using events that are already significant to people as her starting point, she can make experiences that are profoundly meaningful. In detailing her process of working with her participants, she said: “I empathize with their…hopes, and their fears. I build trust, I become their confidant, and I help them to channel their thoughts into a creative container that reflects what is truly important to them.” Her practice is thus founded on authentic listening, which engenders wonder through connectedness.

“The connection found through art is something that is captured rather than invented.”

Emma Sulkowicz also relentlessly pursues truth in her art. Her most famous piece, Mattress Performance, was inspired by sexual trauma that happened in her real life. In her later performances, she has gone even further in working with reality. For example, in Self-Portrait, she answered audience members' questions, but passed along the over-asked ones she no longer wished to answer to a robot version of herself. Reflecting on the performance, she said “I wasn’t changing the way I acted because I was in a gallery. Other people assumed that I would be, because most people really believe in this distinction between art and life, but I’m trying to break down that distinction.” For a more recent piece, The Healing Touch Integral Wellness Center, Emma took on the role of a psychiatrist. My experience of the work was the same as my experience of Emma as a person. In other words, though the work had a specific framework, Emma wasn’t acting. She does not have a medical degree, but she was still her real self in a fictional situation. In a later conversation, she referenced the stereotype that performing artists are performing all the time, even in their real lives. She tries to do the opposite, which is to live her real life even when she’s performing.

It is paradoxical to suggest that the truest intimacy, which is both real and mutual, can be found through art, a medium traditionally thought to be both fictional and unidirectional. I think this paradox rings true because art simply provides a container—a time and space in which we can be with each other—which we don’t often have time to do in the superficial hustle and bustle of our daily lives. The connection found through art is something that is captured rather than invented. As Todd Shalom said to us about his work with Elastic City, “We already have everything that we need, so it’s just a question of reframing.”

...................

ANA FREEMAN was Odyssey Works' 2016-2017 intern, editor of the artists' interview series, and the production manager of Pilgrimage. She also writes for Theatre is Easy and performs with Fooju Dance Collaborative.

Stranger Kindness, a review

How does language make meaning? When we witness a narrative unfolding – especially one that is structured and performed as fiction and thus as a composition to be comprehended – how tightly do the words need to relate to the structure of the story to be relevant? We see it all the time – the words we speak careening from direct communication to a masking of subtext to comfort-inducing digressions. Language folds and overlays and flees meaning and yet somehow we are able to assemble stories from its incredible choreography. Such complexity! And still we find time to revel, on occasion, in the pleasures of language.

Stranger Kindness, a violently disassembled adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, features Marlon Brando’s recorded voice (from the movie) in the role of Stanley Kowalski. It’s a movie I’ve seen countless times – a hot and raw film indulgent with the sweet pleasures of language. The story is a classic tale of a fallen woman, returned to New Orleans after losing everything and leaving her hometown in shame. It’s a story about masculinity and femininity, and the tortuously structured choreography of a woman’s role in a world dominated by men. It is tragic and elegant, and one of my favorite movies. I recommend seeing it.

Then, I recommend going to Stranger Kindness. None of the rest of the lines in the play spoken by the actors are from the actual play. Rather, they speak lines from other plays and other texts. The cast learned the original lines first, along with the original intonation – the accents and the mid-century exuberances – and matched it to the blocking. Then the directors (Lola B. Pierson and Stephen Nunns) replaced the lines with lines from other texts that were relevant but egregiously different. Stella and Blanche and Mitch argue and cry out and insist with complete conviction, but with the wrong words. Sometimes the words are relevant – when Blanche is disappointed by someone’s reaction, she says, for instance, "One day you'll be blind like me and you'll be sitting there a speck in the void," words that get at the emotional valence of the moment but fudge the informational content. Or Blanche’s suitor, Mitch – the man who just might be her last hope for a decent life – while trying to force an unwanted kiss will pronounce feminist critiques, declaring “Woman’s degradation is in man's idea of his sexual rights.”

Sometimes the words themselves are a commentary on the actions of the character – the critic’s voice moving through the scene. Sometimes they are a displacement of meaning. Sometimes they are just funny. The whole experience is uncanny, difficult, and exhilarating. The actors’ exaggerated body language and intonations loudly structure the meanings of their utterances, so that we can pretty much read the intent, but the language they use both undermines and enlightens the scene. We are never certain if the text is text or subtext or commentary or just confusingly relevant; because of this, I spent the entire play as a birdwatcher in a language sanctuary, observing the behaviors of words, seeing how they accrue to meaning and leave it, and occasionally stepping aside from the confusion of it all to wonder at the sublime mechanics of this system we take for granted.

In a nod to the great Polish director Jerszy Grotowsky, the audience is seated above the stage, looking down upon the action. I was not sure why Grotowsky did this, and if there was some meaning in the Acme Corporation’s version it was lost on me as well. There were also a lot of televisions with cut up scenes from the movie occasionally interrupting the action. For me these were helpful as a grounding device, but I suspect there was something deeper intended with them that was lost on me.

The play is also, of course, about mental illness – such a taboo and important subject. I often feel that art is all about mental illness in some way or another – at least the art I enjoy – as it tends to break with standard patternings for “normal” life, working both as a critique of normalcy and a remedy for it. We track mental illness primarily through language. Most markers for madness are perceived through language and, more specifically, through language that deviates from expectation. This production is all about that deviation, so it is appropriate that Blanche only returns to the original text at the end, when she is being carted off by the men in white jackets. It is the title line – her go-to line: that she has “always depended upon the kindness of strangers.” The final note of Blanche’s story is a desperate grasping for a normalcy that will everafter evade her, and one that this adaptation refuses to strive for at all.

The Acme Corporation’s Stranger Kindness is directed by Lola B. Pierson and Stephen Nunns, and is playing at St. Mark’s Church at 1900 St. Paul Street in Baltimore through Dec 17, 2016.

review by Abraham Burickson

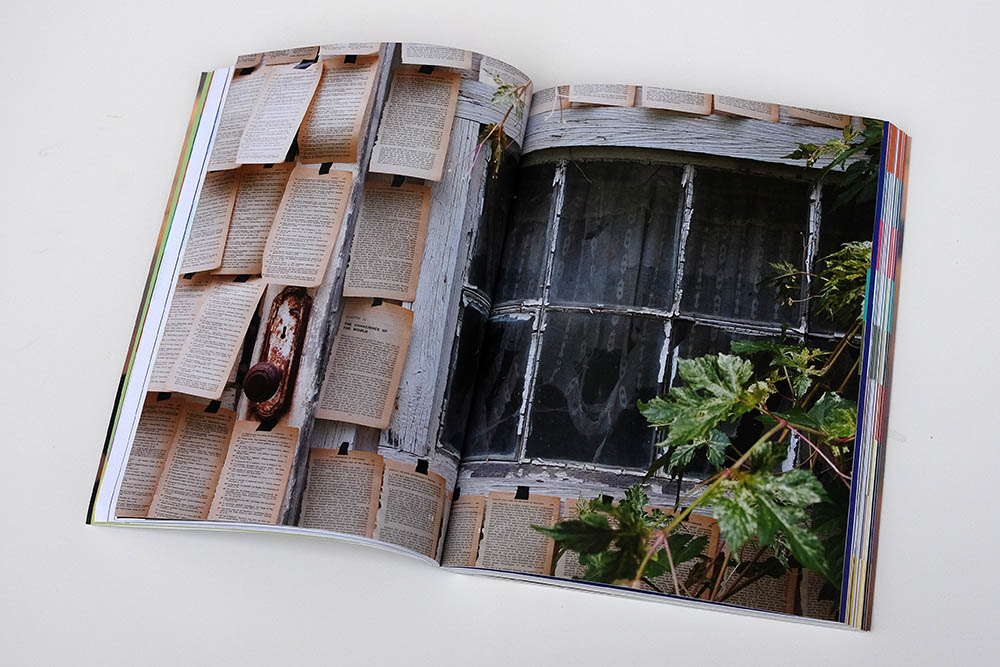

cover image by Tania Karpenkina

After Trump: Why Art Must Go On

I woke up this morning uncertain how I would be able to attend the book release of the book I co-wrote with Ayden LeRoux. It seemed frivolous, like painting the house while Vesuvius is erupting. Add to that the performance I’m producing with the Odyssey Works team this weekend — a thirty-six hour long experience for an audience of one person — an experience aimed at the subtle narratives of that person’s existence, at the interplay between meaning and states of perception, at the potency of empathy. How to do such a thing when facing the reality that a man who has admitted to sexual assault, reveled in racism, and celebrated his megalomaniacal narcissism is now poised to be our commander-in-chief?

On the Art of Relevance

On Wonder (A Review)

OLIVE BIERINGA ON CHOREOGRAPHING EMPATHY

Olive Bieringa. Credit Cameron Wittig.

OLIVE BIERINGA co-directs the BodyCartography Project with Otto Ramstad. The mission of BodyCartography is to engage with the vital materiality of the body in diverse environments. Over the past seventeen years, they have created projects around the world—including interventions in public spaces, large community pieces, intimate museum installations, works for the stage, and short films. Their latest work, closer, premiered in the Twin Cities last year and is now touring. It consists of a series of dance performances for one dancer and one audience member in public spaces, called closer (solo), that multiplies into an expansive performance experience and dance party, called closer (group).

Odyssey Works: How did you come up with the concept of closer, and how did the idea develop from there? What are you trying to do with this work?

Olive Bieringa: We have been working with the idea of choreographing empathy for the past five years.

Our recent work Super Nature was one example. It was a radical ecological melodrama. It took the form of a one-on-one installation combined with an evening-length work for the theatre. We were interested in pursuing a visceral responsiveness in our audiences in order to engage them in a sense of their own animal instinct.

“We use ‘audiencing’ as a verb.”

The idea for closer developed from this concept of a two-part experience, an intimate introduction leading to a larger group work, using the contagion of movement to create transformation in a very personal and direct way.

The piece lays bare the power of physicality and presence and plays with how the meeting between performer and audience member generates the possibility for something new. closer (solo) is an exchange between audience member and performer, an opportunity for self-awareness and self-healing as we practice being present with another person. It is a container for the transmission of embodiment. It also offers our audience a way to reflect on how they watch dance. How do we create meaning and value around our experiences, without judgement? We use “audiencing” as a verb. This is something we can all practice together, experienced dance viewers and novices alike, sharing our resources. closer (group) utilizes the experience audience members have gained in closer (solo). In closer (group), the audience can be anywhere in the space that the performance takes place in, actively pursuing their curiosity. This potentially brings them closer to the work from different perspectives, literally and figuratively.

OW: Why dance in public spaces? How does this change things?

OB: We have been working in public spaces since BodyCartography began eighteen years ago. We are experienced improvisors. It keeps us real. You can never control public space in same way as you can control theater space. Different kinds of environments (e.g. social, architectural, wilderness) inspire different kinds of dances. Our motivations have continued to evolve. Bringing dynamic physical practices, alternative movement behaviors, and engaged embodiment into public spaces, spaces which are often devoid of this kind of consciousness, feels purposeful and meaningful. We meet and dance with people we would not connect with otherwise. In doing so, we create transformation in how people inhabit, use, perceive, and remember public space.

Otto Ramstad performing closer (solo) at Minneapolis City Hall, 2015. Credit Sean Smuda.

OW: closer(group) ends in a dance party. What influence has social dance had on your work?

OB: If we are looking at ideas of physical engagement, it makes sense to invite people further and further inside the work. My passion for dancing was fed deeply on the nightclub dance floor as a teenager. It’s an accessible and celebratory evolution.

Contact improvisation is a social dance form that has had a profound effect on our work. It informs the dancing in closer (solo) in how we use the environment as dance partner.

OW: What is the collaboration between artist and audience as you see it? Where is the artwork itself located?

OB: The artwork is located in the relationship between the performers and the audience, in the bodies of the performers and the audience, in the memory of the performers and the audience, and in our personal interpretations of those experiences.

Kendra Dennard performing closer (solo), 2015. Credit Sean Smuda.

OW: You use the term “presence” to describe your work. What does this mean to you? How does it work and what is the point?

OB: Presence is about being in relationship—with oneself, one’s cells, one’s environment, and other beings. How can we attend to our own internal needs and those of the audience and external environment at the same time? This capacity to fluidly be in relationship amidst many shifting conditions requires porousness and deep self-knowing.

“Everything takes on significance—like somebody turned up the volume on your walk to the corner shop and everything is loud and glowing. ”

OW: Do the experiences you create in closer bleed into the surrounding reality?

OB: In closer (solo), I don’t think either the performer or audience member feel that they are necessarily blending into the surrounding reality, as they are often in a very heightened state of awareness, where everything takes on significance—like somebody turned up the volume on your walk to the corner shop and everything is loud and glowing. Maybe the larger public is completely unaware that an artwork is unfolding around them, noticing only odd moments. For me, closer (solo) can be deeply therapeutic and endlessly challenging. How do I want to spend fifteen minutes of nonverbal time with a complete stranger? How do we find our way through the potential awkwardness to make something shift in the way we are together? Sometimes it's a perfect match. Your audience’s attention and ability to focus is tuned for the kind of dance you are up for creating. Sometimes we just fail. How do we adjust our expectations, our speed, our movement conversation, and have compassion for ourselves and each other? How subtle can a dance or a transformation be? How can being together be enough?

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman.

Maria Hassabi's Plastic, at MOMA, and the Power of Interruption

Dare Turner on Art, Presence, and Gratitude

An image from OW 2014: The Dariad. Photo by Sasha Wizansky

What’s the longest time you have ever spent with a single piece of art?

When I visit museums, I often find myself spending an hour or more with just one piece of art. In my experience, it takes that long to really see it.

Looking at an artwork is a time-based experience; at first glance, it might come off as unassuming and quiet. After ten minutes, you start to notice things you didn’t before—new textures emerge, details become sharper, and colors become more vibrant. By thirty minutes, a piece has started to break through your shell and share its world with you. After an hour, you aren’t looking at the piece anymore; it is looking at you.

Being present, with an artwork no less, is a challenging feat in our modern world. But this is what artworks invite; this is the space they make in our lives, a space for presence. I am incredibly grateful for this.

With Thanksgiving right around the corner, I find myself reflecting on the many things that I am thankful for this year. 2015 has been a truly transformative year, due in no small part to my work with Odyssey Works. The group’s long-duration artworks have changed my perspective on the potential of art. Now I see so many possibilities that weren’t apparent to me before.

At the end of 2014, I received an incredible gift from the Odyssey Work crew: a surprise Odyssey. “The Dariad,” coordinated by Abraham Burickson and my dear friends in San Francisco, offered me the perfect avenue to explore ideas about art that I had been toying with for several years.

Outside of Odyssey Works, I'm a Medievalist, which means that I've spent the past several years studying centuries-old art and ways of seeing that art. The medieval way of seeing is both astounding and incredibly relevant even today. The Middle Ages have gotten a bad rap, going down in history as some sort of backwards-era that offers us nothing more than ugly pictures of baby Jesus. But the art of the period was about so much more than that.

Art from the Middle Ages is all about being present. You can’t see or experience the artwork if you aren’t really there. Medieval art requires patience, longing, and the viewer’s full-bodied participation.

In this way, medieval art theory speaks to and reveals new facets of modern performance artworks, such as that of Odyssey Works.

During the climactic scene of the Dariad, I met a group of around fifty wearing black outside of the De Young Museum in San Francisco. They had gathered for an unconventional tour of the museum, in which we would only view three pieces of art, but spend anywhere from 15-30 minutes with each individual piece.

As we stood in front of a modern-take on an aboriginal sculpture, and a large video installation by David Hockney, I was struck by the medieval-ness of the gathering. By standing in front of a single piece of art for a rather uncomfortable length of time, we had to honestly confront our feelings about a piece, and learn patience.

By engaging with the artworks for minutes, instead of mere seconds, we gave them the chance to look back at us.

During the Dariad, the final artwork that we viewed together as a group was Cornelia Parker’s Anti-Mass. This massive mobile-like piece consists of fragments of a former Baptist Church that had been destroyed by arsonists. The shards of wood are suspended in mid-air, offering a vision of extreme violence and a venue for quiet meditation in the same breath.

Standing in front of this artwork with fifty some people for thirty minutes was a surreal experience. I walked up close to the piece, sat on the bench in front of it, stood at the back of the gallery and waited for the piece to penetrate through my shell—the buffer that protects me, but also separates me from the rest of the world.

Minute by minute, I felt that protective layer dissolve. As every second wore on, I became more present.Anti-Mass crept deeper into my subconscious and altered my understanding of the world. Eventually, I watched my “self” melt away—I became a part of a collective consciousness in that room, communing with art.

Believe it or not, this communal experience is very medieval in its nature. The idea of the “I” emerged with the Renaissance, but the Middle Ages, on the other hand, demanded that egocentric I be subordinated to the collective we. This way of thinking about things may have been mostly lost to time, but in front of Cornelia Parker's work it was entirely accessible. This is the power of art. It transcends time and place; its message can permeate generations and outlast the lifespan of the artist who created it.

It is impossible to experience this and not be grateful.

The Dariad was just one transformative event that Odyssey Works offered me in the last year. Throughout 2015, I have been the acting Public Image Engineer for the group, which has allowed me to explore my creativity on a deeper level and be a key player in running the Kickstarter.

2015 has brought many blessings to the group, most important of which is the incredible outpouring of support that has come through our Kickstarter campaign. Even after months of planning and promoting, I find myself surprised by the fact that over 350 people have donated to the campaign, and that we met our goal after only 15 days!

Both of these wonderful gifts—the Dariad and the success of our Kickstarter—have demanded something important of me: to be present. To actually see the world and not take it for granted. To savor every moment with (or without) art. And to offer gratitude to a world that has blessed me so.

This Thanksgiving, I give thanks to all of you—the Odyssey Works supporters and volunteers that have worked to transform my life and the lives of other art enthusiasts for the better. Though our work might be small in scale, it’s monumental in its effects.

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.