Emma Sulkowicz. Credit Joshua Boggs.

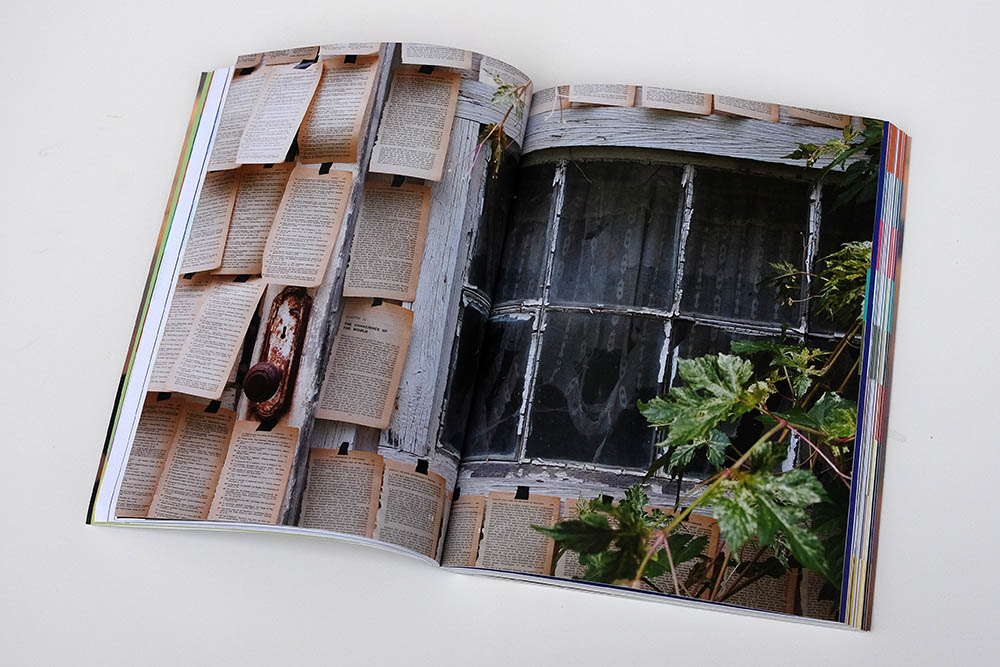

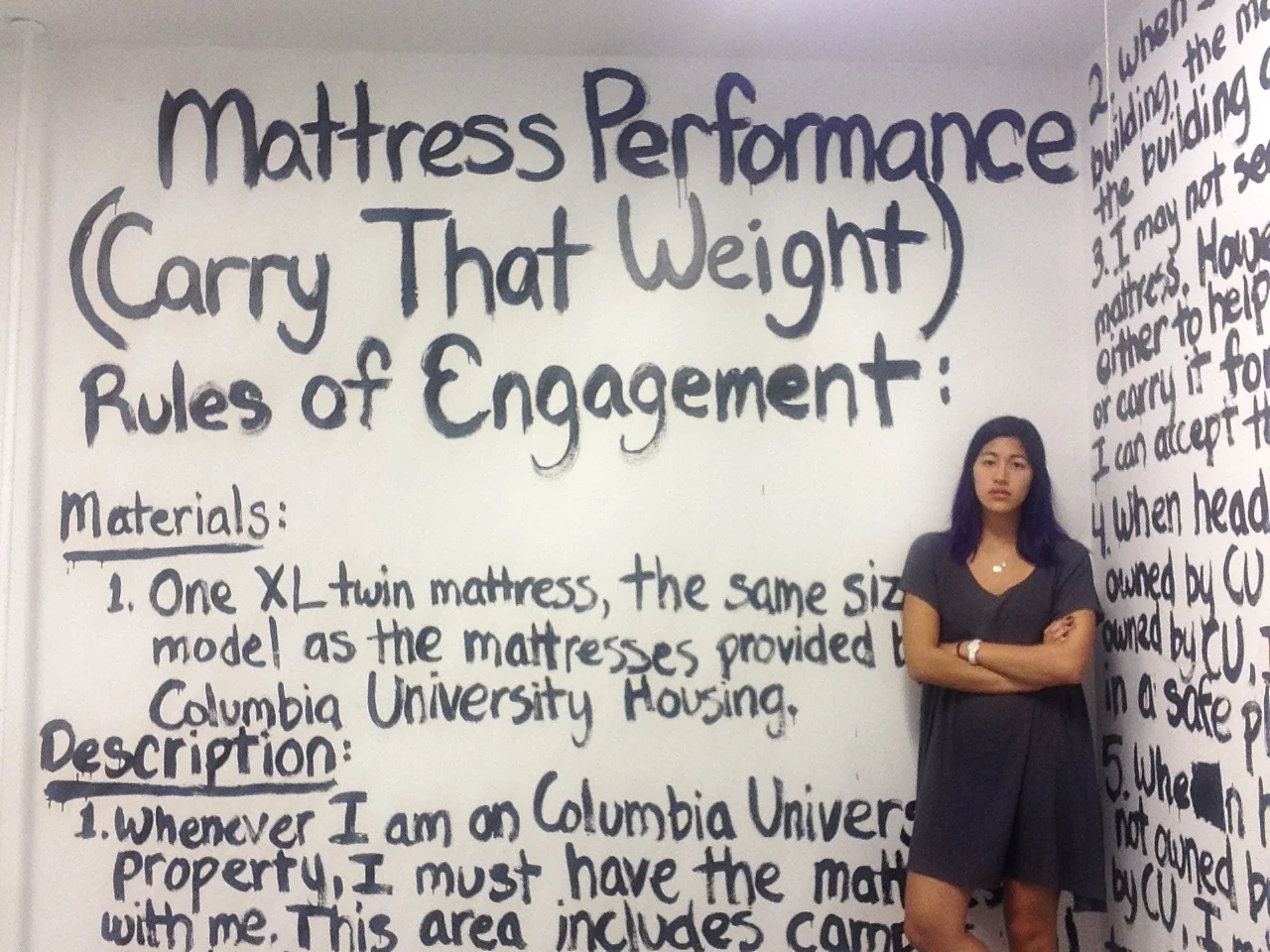

EMMA SULKOWICZ lives and makes art in her hometown, New York City. She is best known for her senior thesis at Columbia University, Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight), an endurance performance artwork in which she carried a dorm mattress everywhere she went on campus for as long as she attended the same school as the student who assaulted her. Her more recent works include Ceci N'est Pas Un Viol, an Internet-based participatory artwork, and Self-Portrait (Performance With Object), in which she made herself available to answer questions from viewers, but referred questions she was not willing to answer to Emmatron, her life-sized robotic double.

Odyssey Works: A lot of the work you do is long durational, and that’s unusual in our age of fast-paced media and fast-paced lives. However, you also heavily utilize technology. What inspires you to work in these differing forms?

Emma Sulkowicz: Well, how boring would it have been if I had carried the mattress for only one day? For that piece, it seemed like long durational performance art was the only form in which anything productive and interesting could happen, given what I was trying to work with. Two of my pieces have been long durational; however, most of my other work is not. I consider myself an artist who works in many different mediums, but for Mattress Performance and Self-Portrait, long durational performance art was the best way to convey my ideas.

All of my work falls under the umbrella of relational aesthetics, which, the way I understand it, includes not just the performance or the objects in the room, but also all the audience reactions to the performance and the objects. Framing things that way changes the way the audience engages with your work. The mattress performance was kind of a crash course in relational aesthetics when I saw how much it took off on the internet, more than it even took off on the ground. So in a way, the technology is unavoidable, because everything, at a certain point, is going to get reproduced for the internet.

The parameters of Mattress Performance. Credit Emma Sulkowicz.

OW: What influences led you to start creating these more experimental kinds of art? And what is your current process like?

ES: I would have to point to a specific moment in time when I went to the Yale Norfolk Residency. You know, when you’re a student, you make a certain type of work that you’re assigned to make, whereas when I went to this residency, and I was so fortunate to be able to do that at such a young age, we were encouraged to make really anything we wanted. That was my first taste of what it’s actually like to be an artist, because once you leave school, no one’s ever going to give you an assignment again. So being in the residency and having all this freedom to make whatever I wanted led me to explore new forms.

When I’m working on a project, I do research. For example, right now I’m working on a piece that would take the form of a fake doctor’s office that would be open for a month. In some respects, I started getting interested in it when I read Derrida’s writings on hospitality. From there, I figure out what I have to read next. Maybe I have to refresh my Lacan, or I have to revisit a Freud essay. One thing leads to another, and throughout my readings, I’m picking up material to use for my art.

And sometimes I find inspiration from more concrete objects or experiences. I did this one piece recently where I saw advertising on the subway for the Alberto Burri show at the Guggenheim that made me really angry, so within the same week I made a counter advertisement of my own and installed it on the subway. I didn’t need any theory for that. It just comes from an impulse. I see something, it either upsets me or gets me excited for some reason, and then I decide how to engage with it. I think that I speak most clearly through my art, so it just sort of naturally comes out as an art piece, rather than, say, an essay.

“I was really interested in the idea that every human being is performing all the time, whether it’s to another person or for themself. ”

OW: Your recent piece in LA spoke to how you are perceived and mediated. And a lot of your other work is in public space and is very engaged with the real world. So how do you view the relationship between reality and performance?

ES: I think that when I began Mattress Performance, I really thought there was a distinction between when you’re performing and when you’re living, and I worked really hard to delineate the two. But whenever I see some sort of binary forming, I try to break it down, so in Self-Portrait, my goal was to perform as my usual self on the platform. I was really interested in the idea that every human being is performing all the time, whether it’s to another person or for themself. I was interested in how people would—because I was on a platform in a gallery—treat me differently from how I expect they would have treated me had we met somewhere else, like at a party. They approached me differently simply because I was in a different space, in a different context—when my assignment, on the other hand, was just to act normally.

I mean, if the person I was talking to was pissing me off, I’d be very blunt with them, and if the person was being really nice and I enjoyed the conversation, I would engage with just as much excitement as I would normally. I wasn’t changing the way I acted because I was in a gallery. Other people assumed that I would be, because most people really believe in this distinction between art and life, but I’m trying to break down that distinction.

Self-Portrait. Credit JK Russ.

OW: Do think that the piece was successful? And how do you define success in your work?

ES: Yes. I learned a lot from it. I saw how some people would come in and really engage with the piece, and would leave feeling like they’d learned something, too, whereas other people would not be willing to give themselves over to the piece, and would then come away from it not having gained anything. For example, this one guy, who was a professor somewhere, came in, sat down on the platform across from me, and just decided it was his time to give me sort of an artful critique. However, he seemed to know nothing about political performance art. You know, I’m really excited to talk to people no matter how much reading they’ve done, but it’s frustrating when they’re then going to feel entitled to educate me on their beliefs, when I haven’t asked them to educate me. His combative mode of conversation was really off-putting. I explained why he was wrong, and I think he left feeling not so great about the piece. Overall, I think everyone’s reactions to the piece were so dependent on how they entered the room. This guy decided that he wanted to have an argument with me, so he left with kind of a sour taste in his mouth. But people who came in wanting to have fun or something like that tended to leave feeling happy. It was full of nuance and different for every person.

I definitely had envisioned it initially as a piece in which I’d show people that I’m human and not this robot they think I am, but as the piece evolved, I realized that actually there was something else going on. A lot of people came not because they wanted to engage with this game of “Is it Emma or Emmatron?” but because they had an agenda for something they wanted to tell me or something they wanted to give me…I can’t even tell you how many people brought gifts. A lot of people brought gifts as if they were offerings, a lot of people cried. That’s not really engaging with the artwork as I set it up, but I realized that everyone had their own agenda for coming.

OW: Mattress Performance was centered around an object that carried a symbolic meaning you and others put on it. Did you consider the mattress a magical object?

ES: I certainly did not, but I think other people did. Marcel Mauss’ A General Theory of Magic is a really interesting book to me. One exercise you can do with that book is actually replacing the word “magician” with “artist” every time it comes up. I think that you can really understand why people might consider the mattress a magical object when you read that book that way.

People would come up to me and say “You know, I’ve been sitting in the middle of campus all day, waiting for you to walk by, so that I can help you carry that.” And I was so surprised. Because to me, at that point…the mattress was dirty. I had to wash my hands after I touched it, it was so gross, and all these people thought they were going to have some crazy transcendental experience touching it? In a certain sense, that does mean it was magical, because if it made people feel a certain way when they touched it, then sure, I guess it worked a kind of magic. But from my perspective, we were really all just touching this dirty rectangle thing.

The sign of the mattress functions on two levels. There’s the purely symbolic level, which bears all this meaning, and perhaps magic, and then there’s the level at which it could have been any mattress. It’s just another object.

“Once a large number of people believe that this magical thing happened, who’s to say that it didn’t happen? ”

OW: What do you see as the purpose of participation in your work?

ES: What I took away from Marcel Mauss’ book is that magic works because people believe in it. There’s an old example in the book, which is Moses at the rock producing water in front of the people of Israel, and Mauss says “…while Moses may have felt some doubts, Israel certainly did not.” Once a large number of people believe that this magical thing happened, who’s to say that it didn’t happen? So, if I didn’t have participants, there would be no magic. And if art is very similar to magic, then there would be no art.

OW: At Odyssey Works, we try to cultivate an inner journey for our participant. Did you feel that Mattress Performance was transformative in this way for you and for those witnessing it?

ES: It was extremely transformative for me. The final product was something entirely different from what I had planned, and it was amazing to see how it took on a life of its own. I am not sure if people were immediately transformed upon seeing the performance in person. However, if we are to believe that it transformed the discourse on sexual assault, it must have been transformative for others. At least, I hope it was.

...................

Interview by Ana Freeman.