Credit Kevin Bertram.

LEANNE ZACHARIAS is a Canadian cellist, interdisciplinary artist, and performance curator. She has been breaking ground in the post-classical music landscape since the 90s, in collaboration with artists of all stripes. Zacharias' ongoing performance project Music for Spaces reimagines concert, public, and natural spaces with sound. Other notable work includes CityWide, which consisted of simultaneous recitals by 50 cellists to open the International Cello Festival, and Sonus Loci, a winter sound installation on Winnipeg’s frozen Assiniboine River. Her cello performance formed the climax of Odyssey Works' piece for Rick Moody, When I Left the House It Was Still Dark.

“A performance works best when everyone feels they are contributing. ”

Odyssey Works: How do you understand immersivity and interactivity? How do they work and what is the point?

Leanne Zacharias: The point is to prevent anyone, audience member or performer, from operating in anything resembling a passive or inconsequential mode. A performance works best when everyone feels they are contributing—via navigation, work, or some form of interaction.

OW: Why create experiences?

LZ: Experiences do more than most performances. They are lived rather than witnessed, so they exist differently in the memory. I think the best art is of this nature. As a performer, the task of creating an experience for someone shifts the intention from self-satisfactory pursuit to gift-giving. In giving a gift to someone, you ask different questions: What do they need? What do they want? What would they like?

OW: What are you trying to do with your work?

LZ: To enable close encounters with live performance, sound, and other people. To create musical scenarios that engage both listeners and players in a more direct way than typical concert settings do. To enhance awareness of gesture, place, and time. To ask what the audience would like that they don't know of yet.

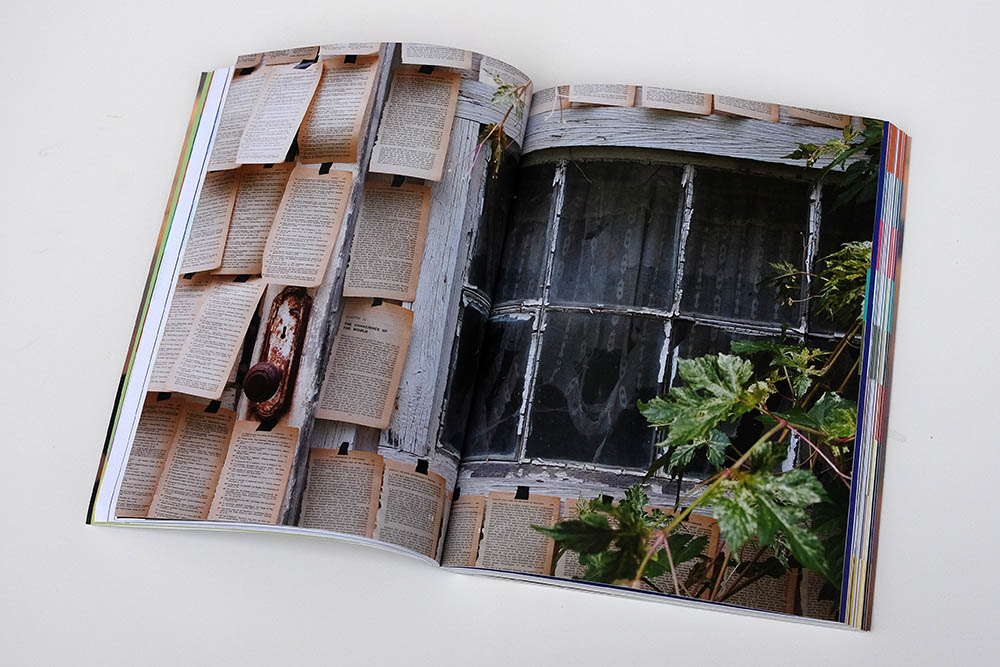

Credit Kevin Bertram.

OW: What is the collaboration between artist and audience as you see it? Where is the artwork itself located?

In many concerts and performance situations, there's little to no collaboration between artist and audience. There's an agreement on the terms, often in the form of a transaction: audience pays admission fee, artist delivers a program. This agreement is a contract and playbook. It outlines expectations. To me, the most interesting place to find the artwork is at the explosion of that transaction—the moment when the audience realizes they're being offered a different type of contract, a new playbook with unorthodox or unclear terms.

“A heightened sensitivity to space, surroundings, and people invites elements of surprise and risk; it requires and builds trust, and creates an exciting tension that is integral to great performance.”

OW: What is the role of wonder and discovery in your work?

LZ: Crucial. If the work is a musical composition, the performer's role is interpretative. Even if a piece has been performed dozens or hundreds of times, it must be made new—through interpretive decisions, its placement in proximity to other musical works, its placement in the environment, or the placement of the performers and audience. Ideally, everyone is experiencing the discovery of a new interpretation of the piece together, in real time. I think of the entire performance, not just the music, as the work, so I attend to all the details: musical landscape, physical landscape, movement, proximity. A heightened sensitivity to space, surroundings, and people invites elements of surprise and risk; it requires and builds trust, and creates an exciting tension that is integral to great performance.

Credit Katalin Hausel.

OW: Who are your influences? Can you describe an experience in which art changed you?

LZ: I'm influenced by knowledge and language beyond my home base in music: architects on community, designers on space, choreographers on movement, visual artists on images and materiality, theatre artists on presentation, and athletes and yogis on repetitive practices. I'm also inspired by naturalists, wilderness gurus, and explorers. I admire their embrace of wildness and their expeditions in search of sudden, fleeting beauty.

My first encounter with Janet Cardiff's Forty Part Motet was significant. It didn't change me so much as distill or crystallize a fundamental part of my identity as an artist. The piece consists of forty individually recorded voices each singing their part of Thomas Tallis' Spem in alium, playing through forty speakers placed throughout the space. It is a stunning, complex installation and a beautiful experience with a single musical work that never changes. Her piece succeeds as a rare opportunity for art-goers to become listeners, and get close to each voice. What it doesn't do is bring the piece to life as a unique performance, or allow listeners to get close to the musicians' real-time efforts, the physical and intellectual work of executing a single part of a grand composition that is unique with each iteration. I had a very strong reaction: I realized my purpose as a musician involves advocating for liveness and finding ways for live performance to involve the level of accessibility, interaction, and immersion of Cardiff's piece. Come to think of it, the experience of performing for Rick Moody in the Straw Bale Observatory is a perfect example of achieving this.

That is, I believe, why I read poetry and seek out jarring art: for a cognitive sneak attack that tricks me into thinking in new ways. It is also why the smart, minimal, dark, rhythmic, unexpected staging of New Paradise Laboratory’s Hello Blackout! won’t leave me alone even now, a month after my having seen it. The piece was choreographed to trick me into thinking in a feeling-being-melancholic way about some big ideas.